|

|

Brian Milani Basic Income

and Real Wealth a discursive review of Raising the

Floor: How a Universal Basic Income can renew our economy and rebuild the

American Dream by Andy Stern (with Lee Kravitz) PublicAffairs Books, 2016 |

|

It’s still only September, but my candidate so far for Significant Economic Book of the Year is Andy Stern’s Raising the Floor. This isn’t because it’s necessarily the best guide to either the basic problems of our economic system or the potentials of postindustrial development, but because it’s the first major expression that I know of, of an influential US labour leader making a strong case for a fundamental break between work and income through the implementation of a Universal Basic Income. That, IMHO, is significant, even if I don’t think Stern is fully aware of the implications of such a break. To growing numbers of activists and analysts, a

UBI, or what I will simply call Basic Income (BI), is one of the most

powerful tools for social change today, one means of attaining guaranteed

economic security for all—which many of us argue is a precondition for real postindustrial development. According to Daniel Raventos (2007), “Basic Income is an income paid by the state to each

full member or accredited resident of a society, regardless of whether he or

she wishes to engage in paid employment, or is rich or poor or, in other

words, independently of any other sources of income that person might have,

and irrespective of cohabitation arrangements in the domestic sphere.” Basic Income can help address some of the most fundamental of capitalism’s structural problems of inequality and scarcity, while also providing a platform to unleash truly regenerative economic development. But doing so requires an unprecedented break from the centrality of the labour market as we’ve known it, something that even the most progressive labour leaders are understandably hesitant to do. What success labour has had to date has been based on workplace organization and achieving power in production. While down through history, unions have often had to respond to technological change with new forms of workplace- and industry-wide worker organization, even labour’s legislative and welfare gains have ultimately been based on strength in workplaces and the labour market. Today, however, real solutions require going beyond the labour market altogether to the economy as a whole. Unionism certainly has an important role to play in this, but it requires a very different mindset about structural change on the part of labour activists as well as the traditional organized left. Andy Stern, former head of the US’s largest union, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), is apparently ready to embrace a new mindset. His main concern is tech change and its impact on job creation, the nature of new jobs, and economic inequality generally. He quit his job as SEIU chief in 2010 at the peak of his power in order to research solutions that he increasingly felt incapable of attaining via conventional union organizing. The book is the product of this research and networking, and is also, not incidentally, a guide for building a powerful social movement to transform the economy. While, as I will discuss, it has some major gaps in both economic analysis and strategy, it covers enough bases to make it a valuable read for anyone interested in economic change. And if one isn’t put off by Stern’s self-referencing style, it’s also an entertaining well-written read that combines analysis with stories and examples from an interesting collection of workers, corporate managers, organizers, investors, activists, economists, engineers and policy-makers. Stern’s strength is in providing an overview—with lots of examples—of current and prospective impacts of robotization, automation, artificial intelligence, etc. and how they are affecting, or will be affecting, the nature of work, or at least jobs and the remuneration of work. His argument is all the more effective because he is not knee-jerk anti-technology. He embraces the positive ways technology can be used and developed, and sometimes even seems uncritical or fatalistic about many aspects of technology (more on that below). But he is very strong in conveying the role of currently-deployed technology in reducing the overall number of jobs, at least good and decently-paid jobs. I knew the situation was bad, but many of his stats on automation, present and future, were still eye-opening.

The book also serves as mini-guide to contingent and precarious labour in the rapidly growing free-agent economy. Although Stern calls attention to how technology and mainstream economic development are affecting those on the margins, he also demonstrates how those margins are expanding and how there are almost no areas of the economy that are not affected negatively by this development. In The Dark Side of the Gig Economy chapter, Stern takes us through his own use of the international Gig Economy to transcribe some of the recorded interviews for his book, spotlighting the situations of the contracted workers he engages. Then he heads to post-Katrina and present-day New Orleans to look at the sad situation of guest workers there who face unbelievable obstacles to both economic survival and basic human rights. He also detours through the dark side of Internet crowdsourcing—exploitative crowd-work that constitutes “an unregulated global labor market where millions of people work for as little as $ 1 an hour or less, without labor protections or benefits.” Besides dealing with the dilemmas that tech change presents, Stern also takes on some of the conventional wisdom about remedial action—in particular the notion that good jobs can be created simply by better education, especially more scientific and technical education. In his Whither the American Dream chapter, Stern looks at both the stats on the projected match between educated workers and available jobs, and some of the grassroots educational initiatives attempting to provide students with the tools to get decent jobs. Neither source gives him any reassurance about future job or income security; quite the contrary. Stern concludes with his solution for these problems, a Universal Basic Income of about $1000 a month for all Americans over 18, along with supplementary measures like raising the minimum wage and a new Stimulus Package. He also provides suggestions as to how to finance the BI, and how to build a campaign of mass education and lobbying (including the creation of a Basic Income political party). |

Basic Income Earth Network on

Raising the Floor The Atlantic magazine on

Raising the Floor Financial Times on Raising the

Floor Robert Kuttner

interviews Andy Stern for American Prospect magazine The Guardian (UK) on Raising

the Floor CBC News: Basic Income: New

Life for an Old Idea CBC: Ontario to Test

Guaranteed-Income Program BIEN-Canada: Income Security

for All Canadians: Understanding Basic Income Huffington Post: Basic Income

Now Official Liberal Party Policy BuzzFlash/Truthout:

Overwhelming Evidence that a Guaranteed Income Will Work Video: interview with Andy

Stern Video: James Mulvale on Basic Income |

|

What’s the Problem? This is very heady stuff for an ex-union leader, but there are nevertheless some major gaps in his analysis, most of which revolve around his failure to question the economic system itself and the direction of economic development. While Stern may be a labour maverick, he still shares some of the economic myopia that has put the trade union movement in such a bind today, and so misses some of the potential of BI for major transformation. That is, unions have focused on achieving a fair share of the economic pie for workers without looking closely at the contents of the pie—at the purpose and social usefulness of the work its members do. Fairness is certainly an admirable quality, but fairness for all, along with the scope of our economic crisis, requires looking more deeply at the nature of work and of economic growth generally. Not incidentally, our very survival on the planet also requires such an examination because the seeds of our current environmental and social crises were planted in the post-WWII Fordist economy of the 50s and 60s that Stern sees so nostalgically as a Golden Age. While he claims that we need to be conscious of larger systemic change over the past 40 years, he stops short of looking deeply at the forces behind the tech change he is so concerned about. He asks “how do we help people continue to make a living, and how do we keep them engaged?” Good question, but a partial one. It has been raised before, after the Great Depression and WWII, but the provisional solutions then, while keeping people busy working and consuming, simply postponed and aggravated the fundamental crisis. Keeping people engaged in a destructive economy is not enough.

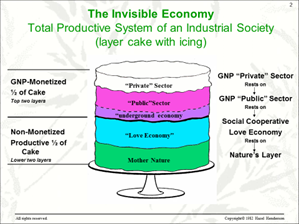

At first glance, Stern seems to zero in on technology as the problem, rather than its use by a profit-obsessed minority. At the beginning of the book, he professes to be quite disturbed at the obliviousness of tech designers to the social impacts of their inventions, especially their lack of concern about creating or maintaining decently-paid jobs. But through the book, he apparently accommodates himself to the inevitability of both the elimination and degradation of work. He seems to think that technology can’t be changed; that it is a neutral uncontrollable given that we must somehow adjust to, ultimately through a universal basic income regime. Real Wealth Stern is clearly very concerned about structural unemployment and growing inequality, and BI can certainly be a big part of countering these things. For many of us, however, unemployment and inequality are symptoms of a deeper economic malaise that Stern doesn’t seem to notice. In particular, there is industrial capitalism’s cancerous economic growth that now threatens the entire biosphere. But also, as Greens and “new economy” activists have been indicating for decades now, almost every sector of the corporate economy could hardly be more inefficient and irrational—in both content and structure—than they currently are in most of the supposedly advanced economies. As a few economists, like the UK’s Martin Whitlock, have emphasized, our modern economies are comprised of ever less useful work—full of middlemen and unnecessary services that take a big cut of society’s real wealth. (Un)economic growth has been directed not just into wasteful material production like arms and suburbs but also into “transactional” work that produces nothing useful in itself. Meanwhile sensible alternatives exist—in local-sustainable

food systems, soft energy path development, eco-manufacturing, Perhaps one reason why Stern underplays grassroots alternatives is

because he is so focused on jobs, while so many of the key alte Golden Age or What? Fordism, Waste and Economic Growth Another reason why Stern misses the need to transform work and economic development more qualitatively may be his infatuation with the post WWII, or what many call the “Fordist”, economy. Such nostalgia is not unusual on the left, given how depressing and unequal Post-Fordism since Reagan has been. The 50s and 60s were times of apparent prosperity, but they nevertheless planted the seeds of our current crisis—especially climate change. In fact, ‘circa 1950’ is a common expert estimate of the onset of the “Anthropocene” era—when humans began to have a decisive impact on the evolution of the biosphere. It’s hard, however, to deny the positive significance of labour gains

after the war. This was the era of

good manufacturing The Great Depression could be considered what Stern might call (but doesn’t) a “strategic inflection point”. It was an unprecedented structural crisis of overproduction. By the late 20s in North America, emerging forces of mass production were beginning to produce way more stuff than workers could afford to buy with their meager wages. While the great crash of ’29 wasn’t essentially different than previous crashes, the ensuing Great Depression was unique, manifesting a longer-term crisis of “effective demand”. By the 60s, Marxian economists like Paul Sweezy would describe this as a new kind of capitalist structural crisis over how the system could “reabsorb” (reinvest or consume) the growing economic surplus without undermining profitability or class power. Class society is based on the control of scarce resources by a minority, and “labour discipline” is threatened when scarcity is eroded. Advocates of FDR’s New Deal argued that addressing this demand crisis necessitated, in addition to more public sector investment, a redistribution of income that would put more money into the hands of worker-consumers. But some New Dealers also recognized that, as the economy began to approach the satisfaction of many people’s basic material needs, it would be necessary to redirect economic development toward greater quality of life. In short, wealth, which was always assumed to mean more stuff and more money, had to be redefined. We had reached a point where accumulation, even more democratically controlled, did not necessarily equate with real wealth creation. Progressives did promote alternative, more qualitative, agendas for postwar economic development, combining more planning with market forces for social purposes. Some intelligent community design, social services and other forms of rational planning were even visible during the war years. But after the war, they lost out to the more wasteful Cold War/Levittown Sprawl model of growth. Real qualitative wealth, like quality of life generally, is expressed in many ways, and reduced paid worktime is one of them. Work time reduction has always been a concern for labour (albeit in widely-varying degrees at different times) for good reason. Free time is certainly no environmental or social panacea; it can be used positively or negatively. But the positive ways can be both a precondition and a vital springboard for the many kinds of regenerative economic activities that make up qualitative development. Thus time, especially one’s truly free time, not forced unemployment or forced domestic work, can be a valuable resource as well as one vital indicator of quality of life. With this in mind, one might think that in any truly developing economy, be it capitalist, socialist or whatever, free time would gradually increase over time if society was truly progressing. From this perspective, note that economist J.M. Keynes believed that, at the long-term rate of productivity growth then (1930), by early 21st century material wealth would have increased 4 to 8 times and people would need only 15 hours of paid work per week. As late as the 60s, sociologists agonized about an incipient crisis of excess leisure time. That clearly didn’t transpire. The economy didn’t stop growing, so what happened? What happened was waste—primarily war production and suburban sprawl, particularly in North America (Europe and Japan had some real rebuilding to do after the war). Conservative elements of the ruling elite noticed that it wasn’t the New Deal and industrial unionism that finally ended the Great Depression, but World War II, a massive mobilization of destruction and waste production. Provoking a Cold War in the fifties would allow the continuance of war mobilization and military production that maintained economic stimulus without much redistribution of income. This wasteful investment was reinforced by

another kind of waste, the so-called Consumer Economy based in suburban

sprawl and fossil fuels. The chaotic

fragmentation of the landscape maximized the consumption of every kind of

material—from From Material Waste to Financialization In the 50s and 60s, authentic economic development needs were effectively subsumed by the new Waste Economy. And even the material gains for the working class began to evaporate by the mid-seventies as the costs of such waste began to come due (via stagflation, state fiscal crisis, health costs, etc.). By the early 80s, Reagan and Thatcher presided over a transition to an even more decadent form of economic growth, reversing the modest material gains of the postwar working class. Controls on people became relatively more financial, especially via many forms of debt. The prevailing neoliberal attitude was to actually overturn labour gains and stimulate growth through special treatment for the rich—starting a long process of increasing income disparity. This might appear to be a return to a Stone Age of “robber baron” market industrialization or even corporate feudalism, but actually it utilized a growing level of advanced information technology.

The “financialization” of the economy, while still based on resource waste, took the level of unproductive “transactional” economic activity to new heights—in effect putting greater emphasis on waste labour and the waste of human potential. At a time when emergent productive forces were ever more connected to the cultivation of human creativity, capitalism began to debase labour with more contingent and precarious work. Since then, the increasing role of culture in the economy has been used not to enrich work, but to degrade and disempower work—witness Wal-Mart’s business model which uses cutting-edge information and logistical systems mainly to drive down labour costs. Even apparently creative work has been channelled into narrow sectors (Richard Florida’s so-called “creative class”) engaged primarily in alienated or destructive forms of economic activity, with much of it also exploited by the freelance “gig economy.” Critiquing technology only in terms of

automation, robotization and job loss completely

misses the biggest problem with technology: its use in the service of waste, artificially-created

scarcity and the suppression of real economic potential. The lack of decent work is just one element

of degradation of the human being in the economy—at a time when human

creative potentials have been increasing. Most of the automation Stern is

concerned about is definitely not economic or efficient for the whole

economy; but it is profitable for enterprises that are allowed to externalize

costs onto everyone else. Financialization since 1980 can legitimately be seen as a hijacking of the information revolution into unproductive activity that shifts ever more existing real wealth to the 1 percent. The Wall Street Casino Economy is now at least as advanced technologically as the military, but is in no way concerned with real wealth creation. And yet, as the dominant economic sector, the priorities of corporate finance are the most influential on overall government economic policy. So we are talking not simply of distorted development of a single sector, finance, but of the undermining of truly productive activity in the entire economy. Paradigm Shift Stern’s view of the economy’s structural crisis, or “strategic inflection point” in his terms, involves a disconnection between economic growth and job-creation. That’s important, but the actual crisis is much deeper—involving a fundamental change in the nature of wealth, and correspondingly in the primary factors of real wealth creation. We are talking about the evolutionary necessity (and capacity) of shifting from quantitative to qualitative development. Today economic growth can only be “sustainable” if it is positively regenerative, contributing directly to both quality of life and ecosystem regeneration. This has strategic implications for the movement against climate change. It means that climate change ‘solutions’ that don’t dramatically increase human quality of life are not real solutions. And further, it makes increasing quality of life the best, and perhaps the only, means of dealing with our fundamental environmental crisis. It can be useful to break down qualitative development into two key

modes: ecological and informational production. They are really just two related aspects of

the growing importance of culture to the economy. For

people, the rise of culture redefines the role of the human in

production—from a source of routine cog-labour to a proactive font of

creativity. This Qualitative development thus isn’t just a new romantic vision, but a survival imperative that is part of a transition from economies based in thing-production to those based in ‘people-production’, or human creativity. It requires both a redefinition of wealth—now taking place through a variety of social and environmental indicators—and a restructuring of the economy. This in turn involves not just a transformation of markets to reflect social and environmental costs and values, but also support for important sources of non-market regenerative wealth that are increasingly outside markets. Both ecological and informational production involve much greater levels of commons-based work. Think of the mass collaboration that created and develops Wikipedia and Linux. Think also of the landscape design and maintenance that harnesses the natural ecological productivity of rooftops, back alleys and city streets. Think also of so many of the other things we share—from city squares to libraries—services economists call “public goods”. A green or postindustrial economy inevitably involves a much greater—and increasing—portion of public goods compared to industrial society. Markets, even transformed ones, can provide only a small portion of this vital production. New forms of remuneration or wealth-sharing are necessary. Qualitative wealth, therefore, demands new forms

of relationship that encourage regeneration.

For both ecological and informational production, property is a

problem. The solution is not banning

it, but making it simply one form of stewardship and/or participation to be

used where appropriate, rather than a right in itself. In a network society, access is more

important Prioritizing People A final point about the difference between qualitative development and industrial mass production: regeneration requires a fundamental means/ends shift that entails a strategic new role for human need. The importance of human creativity means that human development becomes an appropriate goal in itself, rather than a spin-off, side-effect or trickle-down of accumulation, be it material or monetary. Our productive capacities depend upon a generalized expansion of human powers—to everyone, not simply a “creative class” monopolizing key markets and professions. And this requires starting with everyone’s real developmental needs.

Ecologically, the direct targeting of human need is also the fastest

way to conserve natural resources. Lovins (1976) first spotlighted this “end-use” approach

in the 70s with his Soft

Energy Path proposals. He argued

that the sensible priority was to focus on the “hot showers and cold beer” we

want, rather than the power plants and energy sources that are just

means-to-the-end. By starting with

human need, we can work backwards to find the most elegant and efficient ways

to meet this need, saving vast quantities of unnecessary resources. In the 80s, industrial ecologists used this

principle to define the ecological “service Beyond Scarcity: The Fearless Economy One of the great paradoxes of our day is that the vaunted accumulation capacities of industrial capitalism are based in scarcity—both material and cultural. Beyond a certain development level, the only way the system’s perpetual growth can continue without undermining elite power is through waste—and through maintaining scarcity mentalities in the face of potential abundance. Widespread action to attain guaranteed economic security is one of the key means of undermining the scarcity-mentality and unleashing the abundance of human and ecological regeneration. As discussed above, real abundance is qualitative not quantitative; but it does rest on the attainment of material security for all. Over the last several decades, humanity’s productive forces and real wealth have, for the first time, reached a level that can guarantee healthy subsistence for every human being. As Stern rightly points out (citing, among others, Tom Paine, Bertrand Russell and Martin Luther King), achieving the right to live is akin to universal suffrage as an essential step in human social evolution. The quest for this right can, in itself, help to open up discussion about the qualitative dimensions of economic development—be it social or ecological. The fact that we have reached the level of potential abundance—but have not yet manifest it—has made our world a crazy place. Deep down, almost everyone knows things should be different and better, and this creates tremendous tension when people are unclear about how to improve things. The decadent economic landscape is fertile ground for all kinds of scapegoating and escapism—making the world an alienated and dangerous place. While most proponents of BI argue articulately that BI can provide many cost savings and social benefits, even they underestimate, I believe, the potential it has to encourage social harmony and regeneration simply by the reduction of fear. Environmental proponents, e.g., have argued that BI can radically reduce environmental destruction just by giving people the choice to survive without having to do nasty things for a paycheck. This would not only reduce dirty work, but globally also take some of the steam out of escalating resource wars. Economic insecurity—coupled with the bottling up of creative energy—are implicated in most of the world’s main conflicts today.

Today’s capitalist society runs on fear, fear about subsistence that should now be unnecessary anywhere in the world. Innumerable other fears rest on the shoulders of subsistence fear, and many would undoubtedly evaporate if we could achieve universal economic security. From this standpoint, the ultimate weapon in the fight against terrorism may be the same as in the fight against poverty: material security and right livelihood. It seems very unlikely that extremist organizations anywhere could recruit enough testosterone-charged young males if interesting work in, e.g., renewable energy and sustainable food systems was plentiful in their communities. BI in those communities would mean they wouldn’t have to wait for someone to provide “jobs” to start doing this work. BI wouldn’t be a panacea, but would make the task of creating other necessary alternatives far easier. And it would be a major strike against fear. Basic Income and Social Change A green or postindustrial perspective could not view Basic Income, or any kind of material security, as an end in itself. BI not only “raises the floor” of subsistence, but also provides a platform for raising the ceiling on quality of life and regenerative economic activity. Real transformation is required in every economic sector, and BI could make most of it far easier by giving people more freedom. We also should be clear that there are other paths to economic security, including alternative currencies, and infrastructures of free food, housing, education, and healthcare. Mature healthy economies would likely combine several of these means, tailoring them to regional conditions and preferences. But one advantage BI has, at least in winning popular support, is that it is a simple straightforward concept that can be very educational. Lots of people can identify with it, without discouraging different groups and sectors from highlighting BI’s specific relevance to them. Environmentalists may, for example, want to promote the financing of BI through a carbon tax: a strategy that has positive structural implications in itself, since it can help change the balance between labour and resources in the economy. Despite regulation, growing resource depletion, and the increasing degradation of labour, resources are still cheap or free, and labour relatively expensive. This unhealthy labour-resources balance encourages both environmental destruction and the automation/degradation of labour. Climate apocalypse is inevitable unless it changes. Taxing resources and channeling the money directly to people would have a tremendous positive impact that would ripple throughout the economy. Values-driven business proponents—like BALLE, Green for All, etc.—would find BI a God-send, since a working BI program would likely result in an explosion of small smart community-oriented enterprises. The existing job market would be transformed: with business needing to pay workers more for crappy jobs, while being able to pay less for interesting creative work. Alternative financial networks would still be necessary to finance this wave of socially-conscious investment, but it would certainly receive a giant boost from BI implementation. Redirecting the economic surplus away from waste production, extraction, incarceration and gambling will take much more than subsistence for all. But subsistence should make many more things possible. One good thing about BI is that it can work with other measures to ease the transition. Stern, e.g., discusses other complementary measures to deal with

inequality—like raising the minimum wage, a wealth tax, a This review will not attempt to deal with the many others ways (besides a carbon tax) that BI can be financed; there are many. But something must be said about winning popular approval of BI. Stern emphasizes a lowest-common-denominator kind of campaign, so as not to alienate the rich and mainstream politicians. This is understandable because BI really needs to be widely embraced. But it must not preclude being championed by a wide spectrum of people actively engaged in creating alternatives. The democratizing potential of BI shouldn’t be soft-pedalled, especially now, as Bernie Sanders’ campaign dramatized, that there is a growing movement against extreme inequality, political corruption, corporate campaign financing and regulatory capture. Over the long haul, the rise of cultural production not only brings economic decentralization, but also opportunities for more decentralized forms of governance and regulation—that is, direct democracy. While it makes sense to focus on the economic dimensions of BI in an initial campaign, it makes no sense to reinforce undemocratic relationships either. With BI there is also a danger that the gradual process to implement a truly sufficient and universal program could be coopted to become simply a poverty mitigation measure. Half measures could easily make BI just a subsidy for corporate exploitation and an excuse to eliminate vital social programs. While Stern takes his inspiration for a BI campaign from the campaign for Obamacare, more relevant, I feel, would be something closer to the grassroots campaign against SOPA—the draconian Stop Online Piracy Act—in 2011. Then, the politicians’ apparently entrenched commitments to corporate interests shifted overnight under the weight of a viral campaign by open internet activists. BI has the potential to be equally viral. While compromises may be necessary, it is crucial to get the real discussion out of the back rooms and party caucuses and into the public domain. The politicians just have to realize what side their bread is buttered on. Universal Basic Income is a fairly old concept whose time hopefully has come. Because it can play a special role in opening the sky as well as raising the floor, it has special relevance for us today. If it—and other forms of guaranteed economic security—aren’t soon implemented, we are in big trouble, much bigger than widespread unemployment. That said, Stern’s book is a breakthrough, something that may influence many more people to not only look at our economic problems, but also acknowledge some of our potentials. It should be read by as many people as possible. Brian Milani,

Toronto Labour Day 2016 |

|

preventive healthcare, natural building, social finance, and a host of

imaginative new services that were never possible before the information

age.

preventive healthcare, natural building, social finance, and a host of

imaginative new services that were never possible before the information

age. rnatives

involve other kinds of work.

rnatives

involve other kinds of work. jobs,

strong unions, social safety nets, inexpensive public education and reduced

economic inequality.

jobs,

strong unions, social safety nets, inexpensive public education and reduced

economic inequality. concrete

and cars to bungalows and washing machines.

concrete

and cars to bungalows and washing machines. One

reason why

One

reason why